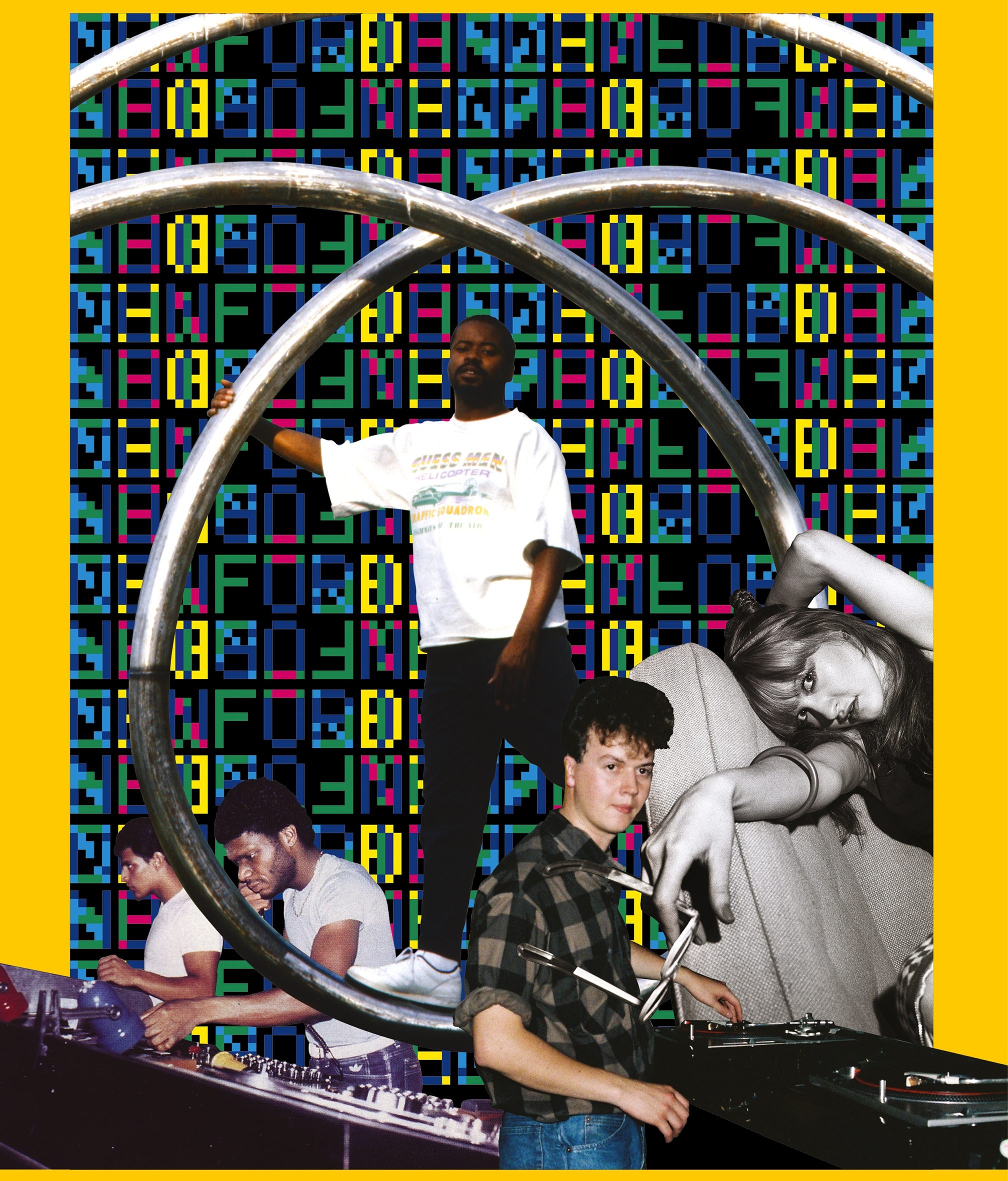

That period in NYC changed popular culture forever

The advent of dance music as a culture unto itself pivots on the year 1984. It was the year Detroit’s Cybotron released their first album, ‘Enter’, and the single ‘Techno City’ gave their post-electro sound a new name and attitude. In Chicago, Larry Sherman opened Precision Record Labs Ltd, promising fast delivery on the records a number of local kids were making with cheap synths and drum machines. Soon the sound would be called ‘house’ – and Sherman would be issuing it on his new label, Trax Records.

But the revolution those styles portended would have to wait a little while. In 1984, club playlists were intertwined with the US pop charts in a way that they’ve seldom been since, thanks to Arthur Baker, François Kevorkian, Shep Pettibone, Jellybean Benitez and Larry Levan giving 12” mixes to tons of major-label pop, r’n’b and rock acts. Not to mention that hip hop blew up harder than ever in ’84, thanks to a raft of breakdancing films and the first Run-DMC album – but hip hop was largely considered just another aspect of dance music back then.

The big new club sound of ’84 was Hi-NRG, which pointed straight back to disco – essentially an update on the synth-led sound of Patrick Cowley’s production work for Sylvester – and ahead to proudly artificial sounds in house, techno, r’n’b and pop. The name came from Evelyn Thomas’s ‘High Energy’, a record that “brought the over-mixed thump back with a vengeance,” as Billboard noted. This iconic gay club anthem would reach the US Hot 100’s lower reaches in September 1984.

Sadly, Cowley didn’t live to see his pioneering work gain traction: he died in November 1982 of what one writer termed “cancer”. Soon it had a name.

Soon after ‘High Energy’ made its impact, the production team of Stock, Aitken & Waterman upped the ante. Mike Stock, the trio’s ideas man, wanted to make “technologically brilliant” records, modeled on Motown, and when he heard Hi-NRG, he recalls, “I knew I could give them exactly what they wanted, with quality.”

Their first salvo of ’84 was a taunt: ‘You Think You’re A Man’, a British Top 20 for Divine, the American drag star of John Waters’ underground films. When the gothy-trashy Liverpool quartet Dead Or Alive approached S.A.W., Pete Waterman recalled, “Pete Burns actually said, ‘Make me sound like Divine!’” The result, ‘You Spin Me Round (Like a Record)’, reached No 1 in the UK in March 1985 and remains a dancefloor go-to – not to mention a karaoke standard. S.A.W. would dominate the rest of the 80s: 13 No 1s, 35 million records sold.

If anyone defined the 12” as the site of aggressive experimentation that still went pop, it was Trevor Horn. That January, the British producer had simultaneous No 1s in the US (Yes’s ‘Owner Of A Lonely Heart’) and the UK (Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s ‘Relax’). ‘Relax’ then re-entered the chart and peaked at No 2 in July, behind its follow-up, ‘Two Tribes’. By the end of the summer, Frankie Goes To Hollywood were estimated to have sold between five and six million records – the vast majority on 12”s. They hadn’t even released an album yet.

On August 6, Horn delivered the keynote address at New York’s New Music Seminar (NMS). That morning, New York Mayor Ed Koch declared it the city’s official ‘New Music Week’, an honour essentially bestowed at the recipients’ request: “Our PR company just went to the city and asked for it,” says NMS co-founder Tom Silverman.

It wasn’t an altogether unreasonable ask. Since 1980 NMS had grown to become the premiere US music biz confab: the 1984 edition had a paid attendance of 3,800. Silverman, who ran rap label Tommy Boy Records, had hit paydirt in 1982 with ‘Planet Rock’ by Afrika Bambaataa And The Soul Sonic Force, which ushered in the next three years’ worth of jittery electro-funk. (Bambaataa was once a marquee participant in the ’84 NMS). Silverman’s partners in NMS were Mark Josephson, who’d co-founded the college-radio trade sheet Rockpool, and Joel Webber of the dance label Uproar. In addition to publishing, Rockpool also “distributed records to DJs that specialised in danceable rock,” says Silverman.

By ’84, pop producers were increasingly adopting dance production tricks: metronomic rhythms that made for easier beat-matching for DJs, bass and drums to the fore, lots of echo intended to be heard whipping around the cavernous spaces of clubs like Paradise Garage. That was where DJ Larry Levan reigned supreme. François Kevorkian, a DJ and remixer who’d got his start in New York clubs in 1977– and in ’83 had done a 12” remix for, of all people, The Smiths – told author Tim Lawrence that “all the DJs from those rock clubs started going to the Garage every week” because “they all had to hear what Larry was playing.”

For Josephson, the club becoming an incubator for pop success was sweet vindication. “Many veterans of the new wave scene are now expressing disappointment that radio, Rockpool and other elements of the infrastructure have gone ‘mainstream’,” he wrote in a Billboard op-ed timed to the ’84 Seminar. “This is a grave misreading… rock’s left wing has not moved to the centre. It is the centre and right wing elements that have moved to the left.”

“By 1984,” says Silverman, “people were seeing a lot of records that were breaking from the clubs” – the ultimate example being Shannon’s ‘Let The Music Play’, a 12” from October ’83 that reached the pop Top 10 in February ’84. It marked the birth of freestyle, a Latin/hip hop hybrid that would emerge as a major late-80s pop style. “Record companies were starting to say, ‘How do we get through to this audience?’ The New Music Seminar was looking at the music industry from the perception of DJs,” says Silverman. “We put together panels about every part of the business, but we loaded the panels with people with DJ sensibilities. The wave we were riding was the growth in DJ culture.”

The New York club that first embraced this hybrid ethos was Hurrah’s, near Lincoln Center. Just as importantly, it was the first New York club to install a giant video screen, with Mudd Club and others following suit. By 1984, video clubs defined the new nightscape. “System installers are working around the clock to meet the demand for hardware as venues from hotels and restaurants to old disco dance clubs are adding the latest technology in hopes of reviving their business,” Billboard reported. One Denver club nearly doubled its attendance after switching emphasis from live bands to video. Gay clubs, in particular, adapted to video quickly: San Francisco’s Midnight Sun, in the Castro; Los Angeles’ Revolver; Chicago’s Berlin and Sidetracks.

The video club ur-model, though, was Danceteria – which, Billboard noted, “provides four floors of entertainment including a concert room, a video lounge, a dance floor and a private lounge for special events. Integrating the modern art world of graffiti artists like Keith Haring to abstract painters and sculptors involves a segment of the population [that] needs an outlet to showcase their work.”

Specifically, Baker was remixing Cyndi Lauper and Bruce Springsteen; the latter attended an overdubbing session for one of the remixes. “The A/C went out,” Baker says. “It was a really hot summer night. Springsteen’s like, ‘Oh man, let me go get a case of beer.’ He got a case of beer, hung with us.” Baker’s first assignment (of three) for Springsteen was to rework ‘Dancing In The Dark’, the single that Bruce had tested out at Club Xanadu in Asbury Park that spring. He wanted to make sure the crowd would dance to it.

Because of the major labels’ new interest in 12”, they began crowding the indie labels, who’d nurtured the format, out of shelf space in stores – a hotly contested state of affairs at the New Music Seminar. “When we do something, the majors let us do it, get the kinks out, and then come with the big money,” said Adam Levy of Sunnyview Records, which struck gold in ’84 with Newcleus’s electro-rap classic ‘Jam On It’. At one NMS panel, a Capitol Records executive said that his label wished to “leave the lion’s share of the 12” market to the indies,” which earned him the vocal approval of co-panelist Cory Robbins of Profile Records, Run-DMC’s label.

He might have preferred Danceteria, but the iconic image of Arthur Baker hustling a new track out for a preview play takes place at a different club: Midtown’s Fun House, which is where, in the video for ‘Confusion’, we see Baker and the members of New Order go to hand over the reel-to-reel master for Jellybean Benitez to test out on the floor. By ’84, though, Benitez had left the Fun House to do studio work full time. He’d become an in-demand remixer, not least due to his work with the woman he was dating. When Jellybean remixed Madonna’s ‘Holiday’ and watched it reach No 16, it was, as Billboard pointed out, “the first Top 40 pop single to be produced by a working club DJ”. He also remixed the follow-ups ‘Lucky Star’ and ‘Borderline’, both pop Top 10s, as well as the title track from Madonna’s second album, ‘Like A Virgin’, which spent six weeks at No 1 starting that December.

Cash Box magazine called Madonna’s success an example of “the co-opting of the dance scene… come full circle.” Sire Records’ Seymour Stein found his biggest catch ever because she was working with (and dating, prior to Jellybean) Danceteria’s Mark Kamins, whom Stein admired. Though he was impressed with her forthrightness, Stein wrote, “there was no reason to believe I was looking at a female Elvis.” Indeed, his boss at Warner Bros., Mo Ostin, refused to sign off on Madonna, figuring her music, Stein writes, as “a downtown dance experiment… pointless 12” bullshit.” Stein quickly learned better: “Madonna was always the smartest person in the room, even when she wasn’t physically there.”