Roland’s 909 drum machine is responsible for the rhythm of house and techno, and countless classics of dance and pop. Exactly 35 years after its launch, we delve deep into the device, learning how it laid the foundations of modern club music, and how it still exerts a strong influence now…

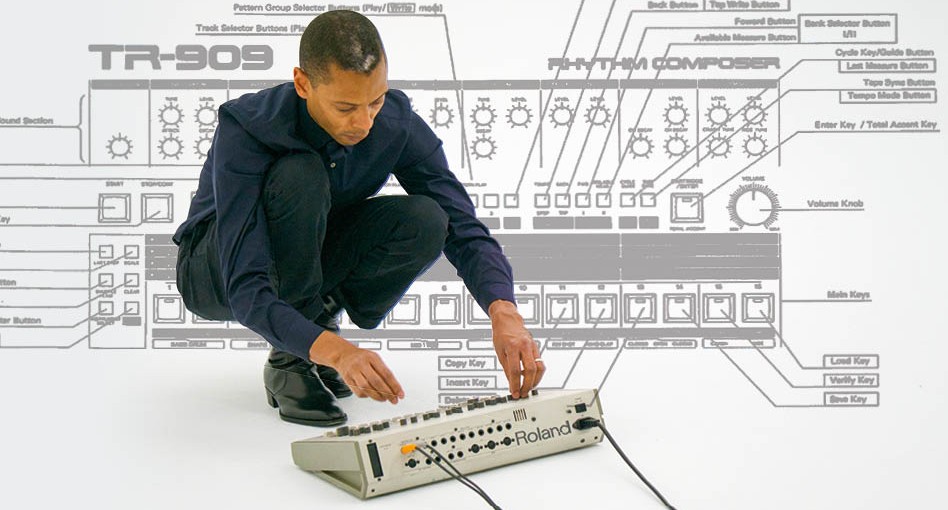

The 909 was Roland’s third rhythm composer. Launched exactly 35 years ago, it followed two other significant machines: the TR-808, probably the most used drum machine in the last 40 years of music, and the TR-606, which was made to partner up with Roland’s TB-303 (a bass synthesiser that accidentally gave us the famous acid sound). The idea of the series was simple — to develop drum machines into drum synthesisers. “Originally, Roland had produced drum machines like the CR-68, CR-800, CR-78,” explain Kenichiro Nishi, a long-standing designer and developer at Roland’s Tokyo HQ, and Atsusi Hoshiai, the original technical engineer of the 909. “In 1980 we produced the TR-808, which was our first ‘drum synthesiser’, where users could edit the sound of each instrument with parameters like tuning, decay, snare snap and level, and then build those sounds into a sequence or song. So, when developing the TR-909, our basic goal was to improve upon our TR-808 with higher quality sound, sequencer improvements and MIDI technology for synchronisation.”

SEQUENTIAL MOVEMENT

Basic goal achieved: like the 808 and the 606 before it, the 909 used analogue circuitry to create most of its drum sounds. However, unlike its predecessors, it boasted much more sonic clarity and punch; it used digital samples for the cymbal and hi-hat sound; had MIDI connectivity and came with additional external memory storage. It offered velocity on each instrument, a preview function, a flam effect (which adds a grace note, or notes, to an individual drum-hit) and the shuffle, which gave the 909 its endearing groove characteristics. It also had the capacity to recall and chain 96 patterns into songs of up to 896 measures, making it Roland’s most advanced and forward-thinking drum synthesiser at the time. Yet, still not hitting the sales Roland expected it to, within a year it went the way of the 808, 606 and 303 and was discontinued in 1985.

“In those days there were many sample-based drum machines,” Nishi and Hoshiai continue. “For example, Linn Drum, Oberheim DMX and the E-mu Drumulator. At the time, the drum machine trend was that of the ‘real sound’, so we feel perhaps the market was not yet ready for the synthesised drum sound that we pursued.”

The market simply didn’t exist. Still in its infancy, electronic music remained the sole preserve of pro studios. Roland’s series was unwittingly ahead of its time, and perfect for home studios and the DIY approach that was about to bloom years later, but not with its original $1,195 price-tag (the modern day equivalent of $3000, which is also the price a well-serviced second-hand one will cost you today). With no home electronic music studios, there was a confusion as to who the machines were for; the 303 was originally marketed as a replacement bass player, so many music shops didn’t know how to sell the 808 and 909. One particularly savvy early customer, however, was Nivek Ogre, singer in Vancouver electro-industrial and EBM pioneering duo Skinny Puppy. Their ‘Remission’ mini-album was released in 1984, just months after the 909 had gone on sale. It’s the earliest example of a 909 on an official release we know of.

INDUSTRIAL STRENGTH

“Skinny Puppy were the only ones I can think of using the 909 as the driving force of their music at that time,” explains Rhys Fulber. A founding member of fellow Vancouver industrial act Front Line Assembly, Rhys has spent the last 32 years neck-deep in synths, with bands such as ambient act Delerium, his solo project Conjure One, and adding 909s to metal acts such as Machine Head, Fear Factory and Megadeth in their remixes. “The ‘Remission’ EP is literally driven by the 909, the whole record it’s right up front,” Fulber continues. “I don’t recall any other industrial bands using the 909 in that way. Even the early New York electro is all 808.”

Electro was the next obvious home for the 909, however. And while much of it was driven by the famous big boom of the 808, Kurtis Mantronik was already incorporating the 909 into his productions, both as one half of Mantronix and producing for other hip-hop acts such as Just Ice, whose debut album ‘Back To The Old School’ featured Kurtis on the cover holding a 909. “Mantronix was one of the first heavy 909 users I knew of,” considers Japanese-born DJ/producer Satoshi Tomiie. “His sound was very hard-hitting and electronic. You didn’t forget it in a hurry. So when house music got introduced in Japan, often from mixes recorded from Chicago radio stations, I was like, ‘Okay, these are the same drum machines from hip-hop’.”

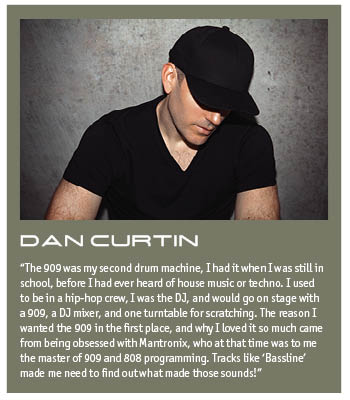

Identification of the sound in the pre-internet ’80s was a factor in the slow growth of Roland’s ahead-of-their-time machines. Satoshi wasn’t alone; it took the most clued-up fans a while to work out what they were hearing. Dan Curtin talks of taking his Walkman to local Cleveland record shops, Jori Hulkkonen would pore over magazines and any music documentaries in north Finland, while Altern-8 co-founder Mark Archer jokes, “Not a lot of people in Stafford in the late ’80s knew about the 909. We didn’t have a chance!” Perhaps if Roland did hang on and continue to make the 909 for a few more years, they might not have discontinued the instrument. By 1986/87, the 909 had infiltrated hip-hop on records by Boogie Down Productions, Ultramagnetic MCs, Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince and Public Enemy (to name but a few). Meanwhile in Detroit, Juan Atkins was knee-deep into his Model 500 project and his Metroplex label, as were seminal Chicago labels such as DJ International and Trax. House and techno were incubating at an accelerated rate, and the 909 was leading the charge.

PROMISED LAND

“When I discovered that motherfucker for the first time and watched them lights come up, it was like having sex,” grins Tyree Cooper. A Chicago OG, he knows the 909 like the back of his finger-drumming hands. Along with producers Lidell Townsell, Parris Mitchell, Joe Smooth and Pete Black, he was behind many of the genre-defining records to emerge at that time, and not just his own.

“There were a lot of ghost writers back then, and I was doing ghost work for DJ International,” explains Tyree, who wasn’t lying when he called himself ‘the producer’ on his famous hip-house anthem ‘Hard Core Hip House’ in 1989. “I won’t say no names, but I learnt the 909 to the point where DJ International’s Rocky Jones would say, ‘Hey, we’ll let you do the drums on these tracks’. I’d say, ‘How much?’ They said, ‘How much you want?’ And I foolishly said I’d take $50 per track. I’d do $300 a week, but them records were selling 20, 30, 40,000! But man, I was studying every inch of that machine like nobody else while I worked on them records.”

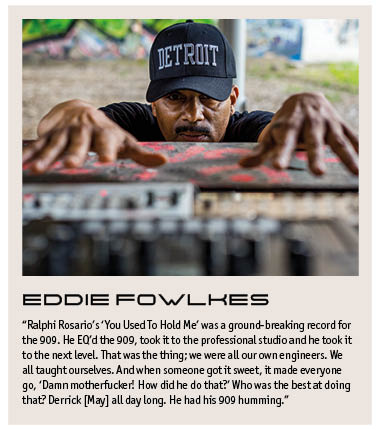

In Detroit, another collective of scholars were refining the art of the 909: Juan Atkins, Kevin Saunderson, Derrick May and Eddie Fowlkes. While their counterparts in Chicago were leaning towards a fat, stripped-back jacking arrangement, Atkins and co honed in on the machine’s shuffle and flam functions, created complex rhythms, bringing the 909’s instantly recognisable and super-crisp hi-hats to life.

“There was quite a bit of a cultural divide at the time,” explains Fowlkes, who picked up his first 909 for $50 at a pawnshop. “You had the hip-hop kids, who were happy to roll with the drugs and make their way that way. And you had the progressive kids who didn’t want to take part in that. We were from the streets, but were more studious about shit. The 909 was perfect for us. We learnt that machine, and EQing was a big part of the art. I know the people in Chicago would EQ their 909s differently to us in Detroit. But it was an underground thing, and respect.”

Fowlkes also elaborates on the classic techno tale of Derrick May selling his 909 to Chicago pioneer Frankie Knuckles. “Derrick quit his job. I thought, ‘How’s he going to pay his rent?’” he recalls. “Next thing I know, someone’s hammering on my door. I think it’s Derrick, but it’s Juan. He’s like, ‘Derrick’s sold his 909 to the motherfuckers in Chicago! What’s wrong with your room-mate, man?’ He gave our weapon to the cats in Chicago.’”

Tyree Cooper confirms validity in that tale, but states Chicago producers were already more than aware of the weapon and many, like himself, Fast Eddie, Chip-E, Larry Heard and Jesse Saunders were all packing 909 heat. However, the plot does thicken: “I think personally when he did sell that drum machine to Frankie, someone else used it to make a house record. Some of the patterns Eddie, Derrick, Juan and Kevin made on it were still on it. I did my homework to work out what it was. It didn’t start house music, that was already happening, but it helped start someone else’s career. That shit’s gonna blow your mind until you work it out…”

MACHINE MOVEMENT

Cooper remains tight-lipped on who that might be, but he’s open about how much of a movement was created when the prices of Roland continued to plummet in second-hand stores and pawn shops. Far from being a weapon, the 909 brought everyone together. “When you’re talking about cultural shifts within music; what motherfuckers can’t afford or can afford is completely influential,” he explains. “You talk about black music in general, hip-hop, house and techno, all these cultures sprang up in a simultaneous way energetically with timeless creation. These machines were what we could afford, and they became the tools of the movement.”

The machines weren’t being used for Roland’s original purpose, but now cheap enough for DIY culture (for the first few years of house and techno anyway), the 909 proceeded to dominate all forms of electronic music from 1989 onwards in every possible direction: from the charts (with the likes of Madonna and Pet Shop Boys flexing the 909s) to the heaviest of DJ sets, such as Jeff Mills’ famous headbending 909 solos. “The 909 produces a very powerful and thick sound,” explains Mills. “This energy that people really wanted to have since the rave era had become even more widespread, so many (like myself) looked for machines that could produce such a result.”

Even when artists couldn’t get their hands on an actual 909 machine, its distinctive sounds echo through samples as well. Lacking the shuffled groove, and often processed in a way that you couldn’t directly achieve in the 909 box itself, these samples would go on to mutate and build on the drum synthesiser’s indelible legacy. Both Kirk Degiorgio and Cristian Vogel explain how they built their own sample libraries, recording drum sounds from their friends’ 909s, while Mark Archer admits to the classic sampling approach. “Luckily, a lot of Detroit tracks broke down into their component parts quite often, which would give us a clear sample,” explains Mark, who would eventually pick up a 909 in Detroit, and whose Nexus 21 track ‘Still Life Keeps Moving’ gave Carl Craig his first remix credit in 1990.

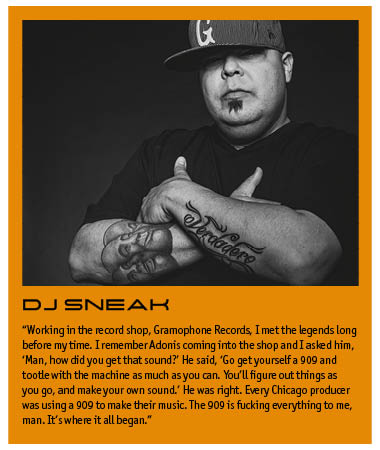

There was also the matter of the 909’s connectivity. As the first Roland machine to ditch the unreliable DIN syncing for MIDI, the 909 could be used to trigger other instruments, and as a clock for the full set-up, with its sequencer central to the whole track as a hub. For DJ Sneak, another Chicago legend, the connectivity was vital. “I could only afford a 909, so I spent a year of making drum tracks and then I got a sampler,” he explains. “And when I synced them, that was the birth of the DJ Sneak sound. So I had all the 909 drums, and the drum sounds and samples I had in the Akai [sampler], which I was shooting back into the 909. I didn’t have a sequencer or money to buy anything else, so it was all done on what I had. ‘You Can’t Hide From Your Bud’ was done on the 909 and S950.”

With the 909 as the hub and sequencer, this meant the machine had a presence beyond its signature drum sounds, or even samples of its drum sounds. Once again, another huge influence of the 909 that Roland didn’t realise they were responsible for, and another example of how the artists who wrote many of the records that shaped dance music were pushing machines to do things they weren’t really supposed to be doing.

“As embarrassing as this is to say,” admits Roland’s Hoshiai and Nishi, “it took us quite a while to realise this fact. When we did notice, we made the decision to develop our first product that focused completely on club-style music, the MC-303 Groovebox, which was released in 1996.” While an impressive, intuitive hands-on machine, the Groovebox had arrived too late for many; the 909 and its older brothers the 808, 606, its younger brother (the live-sounding digital-sampling 707) and, of course, the 303, had entrenched themselves into electronic music forever.

“Roland did a lot,” considers Saytek. One of the few contemporary producers in this discussion, he doesn’t own a physical 909, but favours its emulators instead, and has a deep respect for what it’s done for music. “Where would we be without the 909 and 808? Would the music have even evolved in the way it did? These machines weren’t even designed for dance music, dance music didn’t exist in this way when they were launched, yet the sound of a 909 defines house and techno. The clap, hi-hat, the kick, the rimshots, the toms. Even without knowing, everyone knows the 909 sound.”

It seems many of them are returning to it, too. Roland’s long-awaited relaunch of the machine in the form of the TR9 last year was received with critical acclaim, while many artists are trying to reduce screen time and return to the raw, physical hands-on feeling the founding house and techno fathers enjoyed when they embraced Roland’s machines and squeezed them for every bit of electronic music essence and spirit. Leading Berlin techno artist Cinthie has just built her new studio with a whole analogue armoury… and she quit her job as a music software programmer in the process.

“I worked for Ableton as a software developer for years,” she says. “But I got bored of moving the mouse around. With software, everything is mathematical. Over time, the old machines get a little wonky. They don’t sound 100 percent clear sometimes, and they don’t all sound like each other. They develop their own character. They are human, and music should be, too…”

For the final word we turn to one of the undisputed 909 masters, Jeff Mills. Almost 30 years after he bought his first 909, he continues to use it in his live sets, and creates insane 909 workout videos under his Exhibitionist series. If there’s one man that faithfully captures the true spirit and essence of the Roland TR-909 Rhythm Composer, and who can consider how it might be developed, or made even better, it’s him.

“I think the machine is getting all the attention it deserves,” he concludes. “It’s an incredible machine, if applied properly. Unfortunately, the TR-909 only has 10 sounds, but if it had more to consider, this might have had an effect as well. For instance, if it had a cowbell or tambourine. Imagine the possibilities…”